Saturday, October 17, 2009

THE RICH HAVE STOLEN THE ECONOMY

From Offshoring Jobs to Bailing Out Bankers

Originally published here on counterpunch.org

I don't give a fuck about "the terrorists". These people are worse than the terrorists. I can understand why someone in the middle east hates America. It has been American bombs falling on their villages for the past EIGHT years. Why shouldn't they hate us, or want to hurt us? It makes perfect sense.

These corporate sons of bitches, however, are much worse. They hurt us, many more of us, than "the terrorists" have. And they live here. Their only loyalty and goal is to make as much money as they can, by destroying our lives. They destroy America, and we're supposed to look up to them as icons of what "The American Dream" can result in. If YOU TOO work hard, get ahead, and study, one day you won't just work in the factory... you will be able to PROFIT by offshoring the factory, thus destroying the lives of your former coworkers.

We Must Overthrow The Dictatorship Of The Capitalists

-CW

By PAUL CRAIG ROBERTS

Bloomberg reports that Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner’s closest aides earned millions of dollars a year working for Goldman Sachs, Citigroup and other Wall Street firms. Bloomberg adds that none of these aides faced Senate confirmation. Yet, they are overseeing the handout of hundreds of billions of dollars of taxpayer funds to their former employers.

The gifts of billions of dollars of taxpayers’ money provided the banks with an abundance of low cost capital that has boosted the banks’ profits, while the taxpayers who provided the capital are increasingly unemployed and homeless.

JPMorgan Chase announced that it has earned $3.6 billion in the third quarter of this year.

Goldman Sachs has made so much money during this year of economic crisis that enormous bonuses are in the works. The London Evening Standard reports that Goldman Sachs’ “5,500 London staff can look forward to record average payouts of around 500,000 pounds ($800,000) each. Senior executives will get bonuses of several million pounds each with the highest paid as much as 10 million pounds ($16 million).“

In the event the banksters can’t figure out how to enjoy the riches, the Financial Times is offering a new magazine--”How To Spend It.”

New York City’s retailers are praying for some of it, suffering a 15.3 per cent vacancy rate on Fifth Avenue. Statistician John Williams (shadowstats.com) reports that retail sales adjusted for inflation have declined to the level of 10 years ago: “Virtually 10 years worth of real retail sales growth has been destroyed in the still unfolding depression.”

Meanwhile, occupants of New York City’s homeless shelters have reached the all time high of 39,000, 16,000 of whom are children.

New York City government is so overwhelmed that it is paying $90 per night per apartment to rent unsold new apartments for the homeless. Desperate, the city government is offering one-way free airline tickets to the homeless if they will leave the city. It is charging rent to shelter residents who have jobs. A single mother earning $800 per month is paying $336 in shelter rent.

Long-term unemployment has become a serious problem across the country, doubling the unemployment rate from the reported 10 per cent to 20 per cent. Now hundreds of thousands more Americans are beginning to run out of extended unemployment benefits. High unemployment has made 2009 a banner year for military recruitment.

A record number of Americans, more than one in nine, are on food stamps. Mortgage delinquencies are rising as home prices fall. According to Jay Brinkmann of the Mortgage Bankers Association, job losses have spread the problem from subprime loans to prime fixed-rate loans. At the Wise, Virginia, fairgrounds, 2,000 people waited in lines for free dental and health care.

While the US speeds plans for the ultimate bunker buster bomb and President Obama prepares to send another 45,000 troops into Afghanistan, 44,789 Americans die every year from lack of medical treatment. National Guardsmen say they would rather face the Taliban than the US economy.

Little wonder. In the midst of the worst unemployment since the Great Depression, US corporations continue to offshore jobs and to replace their remaining US employees with lower paid foreigners on work visas.

The offshoring of jobs, the bailout of rich banksters, and war deficits are destroying the value of the US dollar. Since last spring the US dollar has been rapidly losing value. The currency of the hegemonic superpower has declined 14 per cent against the Botswana pula, 22 per cent against Brazil’s real, and 11 per cent against the Russian ruble. Once the dollar loses its reserve currency status, the US will be unable to pay for its imports or to finance its government budget deficits.

Offshoring has made Americans heavily dependent on imports, and the dollar’s loss of purchasing power will further erode American incomes. As the Federal Reserve is forced to monetize Treasury debt issues, domestic inflation will break out. Except for the banksters and the offshoring CEOs, there is no source of consumer demand to drive the US economy.

The political system is unresponsive to the American people. It is monopolized by a few powerful interest groups that control campaign contributions. Interest groups have exercised their power to monopolize the economy for the benefit of themselves, the American people be damned.

Paul Craig Roberts was Assistant Secretary of the Treasury in the Reagan administration. He is coauthor of The Tyranny of Good Intentions.He can be reached at: PaulCraigRoberts@yahoo.com

Originally published here on counterpunch.org

I don't give a fuck about "the terrorists". These people are worse than the terrorists. I can understand why someone in the middle east hates America. It has been American bombs falling on their villages for the past EIGHT years. Why shouldn't they hate us, or want to hurt us? It makes perfect sense.

These corporate sons of bitches, however, are much worse. They hurt us, many more of us, than "the terrorists" have. And they live here. Their only loyalty and goal is to make as much money as they can, by destroying our lives. They destroy America, and we're supposed to look up to them as icons of what "The American Dream" can result in. If YOU TOO work hard, get ahead, and study, one day you won't just work in the factory... you will be able to PROFIT by offshoring the factory, thus destroying the lives of your former coworkers.

We Must Overthrow The Dictatorship Of The Capitalists

-CW

By PAUL CRAIG ROBERTS

Bloomberg reports that Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner’s closest aides earned millions of dollars a year working for Goldman Sachs, Citigroup and other Wall Street firms. Bloomberg adds that none of these aides faced Senate confirmation. Yet, they are overseeing the handout of hundreds of billions of dollars of taxpayer funds to their former employers.

The gifts of billions of dollars of taxpayers’ money provided the banks with an abundance of low cost capital that has boosted the banks’ profits, while the taxpayers who provided the capital are increasingly unemployed and homeless.

JPMorgan Chase announced that it has earned $3.6 billion in the third quarter of this year.

Goldman Sachs has made so much money during this year of economic crisis that enormous bonuses are in the works. The London Evening Standard reports that Goldman Sachs’ “5,500 London staff can look forward to record average payouts of around 500,000 pounds ($800,000) each. Senior executives will get bonuses of several million pounds each with the highest paid as much as 10 million pounds ($16 million).“

In the event the banksters can’t figure out how to enjoy the riches, the Financial Times is offering a new magazine--”How To Spend It.”

New York City’s retailers are praying for some of it, suffering a 15.3 per cent vacancy rate on Fifth Avenue. Statistician John Williams (shadowstats.com) reports that retail sales adjusted for inflation have declined to the level of 10 years ago: “Virtually 10 years worth of real retail sales growth has been destroyed in the still unfolding depression.”

Meanwhile, occupants of New York City’s homeless shelters have reached the all time high of 39,000, 16,000 of whom are children.

New York City government is so overwhelmed that it is paying $90 per night per apartment to rent unsold new apartments for the homeless. Desperate, the city government is offering one-way free airline tickets to the homeless if they will leave the city. It is charging rent to shelter residents who have jobs. A single mother earning $800 per month is paying $336 in shelter rent.

Long-term unemployment has become a serious problem across the country, doubling the unemployment rate from the reported 10 per cent to 20 per cent. Now hundreds of thousands more Americans are beginning to run out of extended unemployment benefits. High unemployment has made 2009 a banner year for military recruitment.

A record number of Americans, more than one in nine, are on food stamps. Mortgage delinquencies are rising as home prices fall. According to Jay Brinkmann of the Mortgage Bankers Association, job losses have spread the problem from subprime loans to prime fixed-rate loans. At the Wise, Virginia, fairgrounds, 2,000 people waited in lines for free dental and health care.

While the US speeds plans for the ultimate bunker buster bomb and President Obama prepares to send another 45,000 troops into Afghanistan, 44,789 Americans die every year from lack of medical treatment. National Guardsmen say they would rather face the Taliban than the US economy.

Little wonder. In the midst of the worst unemployment since the Great Depression, US corporations continue to offshore jobs and to replace their remaining US employees with lower paid foreigners on work visas.

The offshoring of jobs, the bailout of rich banksters, and war deficits are destroying the value of the US dollar. Since last spring the US dollar has been rapidly losing value. The currency of the hegemonic superpower has declined 14 per cent against the Botswana pula, 22 per cent against Brazil’s real, and 11 per cent against the Russian ruble. Once the dollar loses its reserve currency status, the US will be unable to pay for its imports or to finance its government budget deficits.

Offshoring has made Americans heavily dependent on imports, and the dollar’s loss of purchasing power will further erode American incomes. As the Federal Reserve is forced to monetize Treasury debt issues, domestic inflation will break out. Except for the banksters and the offshoring CEOs, there is no source of consumer demand to drive the US economy.

The political system is unresponsive to the American people. It is monopolized by a few powerful interest groups that control campaign contributions. Interest groups have exercised their power to monopolize the economy for the benefit of themselves, the American people be damned.

Paul Craig Roberts was Assistant Secretary of the Treasury in the Reagan administration. He is coauthor of The Tyranny of Good Intentions.He can be reached at: PaulCraigRoberts@yahoo.com

Tuesday, October 13, 2009

A Rather Brief History of Industrial Music

*************** If you are a slow or distracted reader it is will be more efficient if you just read this instead. Then come back here and skip down to the chapter on the "Parodic Phase" of Industrial. You'll get the gist *************

"To escape the horror, bury yourself in it."

-Genet

In the mid to late 1970s a new musical movement, known as punk, emerged in the United States and England, quickly spreading to other countries. The history of Punk itself can, and has, filled volumes, and my purpose is not to recount or critique it here. For our purposes, Punk is significant for ONE reason: It blew the lid off established musical forms and opened the door for a resurgence of innovation.

The number of genres and sub genres that look to punk as musical forefathers is vast. Post-Punk, Hard Rock, Goth, Death Rock, Industrial, EBM, Indie Rock, Emo, Grunge, Metal, Future Pop, Power Noise, etc... all owe a greater or lesser debt to the accomplishments of a rather small number of people banging their fists against the mainstream for a couple of years in the 1970s.

The purpose of this document is not to explain all of them, or even to explain the rise and fall of different bands, labels, individuals, and scenes within Industrial Music in depth. For that I will refer you to the rather good Wikipedia article on this topic. Here I am only providing a rough outline to convey the basics of what different phases the genre has passed through, from its origins, to its current parodic death throws.

This transformation can be appreciated by focusing on five distinct periods of development.

I) The First Wave of Industrial Music

II) Electronica + Sampling & The Golden Age of Industrial

III) Evolution + The Aggro-EBM of the late 1990s

IV) The Wilderness

V) Parodic Phase

Industrial has traditionally be characterized as a percussion- intensive genre. This is generally true, however it has been as much focused on simple audio experimentation as it has been with the aesthetic of people banging on things. Take Throbbing Gristle- one of the first "industrial" bands. Using effected guitar and bass, primitive synthesizers, tape loops, and random additional instruments, they created very strange sound-collages that did not generally fit into the traditional "song" structure. If Richard Wright of Pink Floyd was one of the first to use synthesizers as an integral part of pop music in the 1970s, Throbbing Gristle, and their peers in this time (Bands such as Cabaret Voltaire, SPK, Monte Cazazza, Einstürzende Neubauten) were still trying to use- anything and everything - to push and break the limits of what we consider "music".

How about replacing an electric guitar with a Jack Hammer? How about using bits of pipe, scrap metal, and oil drums, instead of traditional drum sets? What better way to reflect (or encourage?) the decay of late industrial society than by appropriating the actual material, and organic sounds, of this society? Punk had thrown open the doors for intelligent people to think about fashion, music and art in different ways... but for all its rage and fury punk has also remained one of the most musically conservative of all genres, hardly ever deviated from the traditional "rock" instrument line up. Industrial people were too creative and adventurous to limit themselves to this.

In the early days, synthesizers were A LOT more expensive than they are today. As a result, few people could afford them. There were no computers and Midi Controllers to set up in one's bed room and "mess around" on. Furthermore, Digital Samplers were not readily available until the early 80's and even by then they were in short supply, very expensive, and had very limited memory and sampling rates. If, instead of a traditional "snare" drum, you wanted the sound of metal on concrete, or metal on metal, you had to actually get those real objects and carry them to a show and bang on them then. As a result, live performances of "industrial" bands in the 70s and 80s were generally more interesting than those of "industrial" bands today.

For an example, see the following early Neubauten clip:

Chaotic noises, the clanging of metal, "industrial" clothing, situations, etc... and some tortured screams to boot. The elements are here in place.

Meanwhile in England a very similar group, Test Department, also could not afford synthesizers. As a result they were able to create, in a far more structured and upbeat way, some of the greatest performances in the history of this genre. The following three videos, for Total State Machine, Compulsion, and Gdnask, will leave you with a good idea of what "Industrial Music" was able to accomplish in its early days.

At this point the basic political / worldview that has been shared by most industrial acts since the beginning should be clearly evident. The world is an unjust furnace of heavy breaking things where people toil and die and are kept in check by a system of official repression as well as ideological confusion. Banging on scrap metal "for arts sake" is always fun... but ideology and political confrontation, whether it was in Test Dept's support of the anti-Apartheid movement in South Africa, or Skinny Puppy's animal rights focus and antiwar messaging, Leatherstrip's anti racist and anti religious album Underneath the Laughter, or Laibach's entire existence... a polemical, political agenda has usually been present.

Laibach, the Slovenian group founded in 1980, began in a very similar situation as Test Department, although on the other side of the "Iron Curtain". Living in "Communist" Yugoslavia, a likely method of rebellion would have been something as predictably degenerate and Western as punk. But these four were a lot more subtle in their rebellion. Instead of frontally attacking the edifice of Stalinist dictatorship, they emulated it even more thoroughly than their own Titoist rulers. Officially, Yugoslav society rested on an assumption of shared ownership, sacrifice, and cooperative living. In reality, social class did exist, and it was upheld with force. Laibach seized on the darkest, most extreme totalitarian impulse and developed it in their music, which was a lot harder for the authorities to understand (let alone repress, when outwardly the band was proclaiming their reverence for the state... even while their own exuberance betrays its brutality and shortcomings).

Here is the music video for one of their best songs, off the Opus Dei record. This song, Geburt Einer Nation, is a cover of One Vision by Queen.

The stunning visuals are no isolated coincidence. In 1983 Laibach helped to found Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK), an artists' collective with architectural, graphic design, videography, and musical departments, that assumed the identity and structure of a universal, planned "state", far out doing the official totalitarian one in the thoroughness and order of its vision.

Not surprisingly, Laibach's first releases in the west were met with skepticism, with many confused observers writing them off as some kind of Fascist or Communist hobgoblin. For more on the interesting early days of this project (up to the early 90s), see this wonderful 6 part documentary.

If synth-laden "New Wave" secured a dominant position in the pop of the 1980s, the growing accessibility of keyboards and sampling technology brought with it an evil twin who would lurk the shadows throughout the decade. Skinny Puppy, Front 242, Ministry, Revolting Cocks, Numb, The Legendary Pink Dots, KMFDM, My Life With the Thrill Kill Kult, Die Warzau, X Marks the Pedwalk, Leaether Strip, Front Line Assembly... to name a few. Several of these acts originated in Canada, and as this "second wave" of industrial grew into a more coherent scene, the memberships of many different acts would overlap, spinning off a series of guest appearances, side projects, and "supergroups" like Pigface and Revolting Cocks who've left their legacy in countless youtube videos, fanatically collected and traded bootlegs, rare vinyls, and general nostalgia.

Listening to any of these bands you'll quickly notice the important of synthesizers. In addition, the use of samplers meant that, rather than dragging an entire construction site on stage a la Neubauten, one could simply take a tape recorder to the construction site, and later re-create "industrial" soundscapes in the studio. Bands needed less (though still a few) members, but fewer people could sonically accomplish quite a great deal more, running synthesized and recorded ambiance, "found sounds", and yes, even disturbing vocal clippets from films, radio, or television, through a series of filters and multi effects.

This video from "Worlock", is probably Skinny Puppy's best known song. It was banned when released to due to inability to get clearance from so many film studios for lifting clips from horror films. Bootlegs used to be sold back and forth over ebay by fans. Now youtube finally brings it to everyone:

A good way to characterize skinny puppy's sound is "Wet". Erie strings, bloody samples, reverb, delays, etc... are literally dripping off and over a steady beat, as they set out to portray a frightening world as seen from the standpoint of, well... a mistreated dog. This style was developed within Puppy and a series of spin offs and side projects (aDuck, Hilt, Doubting Thomas, the Tear Garden, CyberAktif, oHgr, and Download, to name several).

A bit of a counter point maybe found in the rise of "EBM", or "Electronic Body Music". Using drum machines, at times live drummers, and fast, arpeggiated bass lines and synth leads, this term was first coined by Front 242. While similar in a lot of ways to "wetter", more experimental bands like Numb or Puppy, EBM has generally been "tighter", faster, and more specifically made for the dance floor.

This is really a terribly over-played song... but as pretty much all of 242's official videos are pretty cheezy & 80s, this one is at least a bit more interesting than many.

If you're wondering why the guys in that film look like they are fighter pilots or something, well, that is part of the martial EBM aesthetic. It's ironic that many "industrial" nights now a days alternate playing bands like this, and playing "80s" music that bands like this were in their own time rebelling against. If Duran Duran and Tears for Fears were writing pop songs to dance and have fun with, 242 and Front Line Assembly were interested in a more "martial" approach that engaged with all the frankness (and influences) of a war correspondent what exactly was happening in the world. Naturally many of their songs happened to be about war, and were rather a bit dark with post - apocalyptic themes predominating. Alternately, synthpop was always more concerned with trying to hide from reality- preferably in the comfortable arms of a lover.

As another example, here we have the hit "Plasticity" by FLA:

Within EBM, not all the focus was as dark. A few "Funk-Industrial" bands, like Nitzer Ebb and Die Warzau, developed out broader musical influences in the late 80s:

EX: Strike to the Body by Die Warzau:

In a similar vein, My Life With the Thrill Kill Kult took satanism, drugs, sex, and a drum machine, and turned it all into a rather upbeat dance act:

In the 1990s many different things happened to Industrial- some good and some bad- but all were transformative, and it would be impossible to understand the genre today without a look at these processes as they unfolded over the decade.

Of course, a few bands from the early days broke up or took long breaks (though a surprising number continued), and a few drug related deaths did occur (leading most notably to the demise of Skinny Puppy in 1995). Of the bands that remained, a lot began to change their sound, perhaps bowing to commercial pressure by breaking into more commercially acceptable genres, or perhaps simply because it is unrealistic to expect an artist to make the same album every time. Sometimes this worked for the better and sometimes for the worse.

However, commercialization and the watering down of experimental origins certainly did take place.

For example, many fans of "metal" music today know about and love Ministry, which ever since The Land of Rape and Honey album has pretty much relegated electronics to the far sidelines... for all intents and purposes Ministry has been a metal act since then. Prior to this occurrence, here is a song off the EBM/ industrial album Twitch (1986):

Here's "New World Order" of the later Psalm 69 (1991) album.

You'll notice there's a few faint repetitive sampled sounds that add to the rhythm. But by this point, electronics are pretty much gone, and guitars have taken over.

For an oft-note-and-denounced of example of commercialization, see "Down In It", by Nine Inch Nails, which lifts the rhythm and guitar part from "Dig It" by Skinny Puppy. While Puppy's track was generally dark, distorted, and far less accessible to the masses, the NIN track is far more polished. If Marilyn Manson cashed in on the latent commercial potential of Goth, NIN more than any other band can be said to have done so for industrial.

* * *

On the plus side, a new generation of musicians who grew up listening to Puppy, FLA, and the Wax Trax! record label were now making their own music, and a lot of it in the mid-late 90s seemed promising. Changes took place both in aesthetics as well as technology. Synthesizers continued to fall in price and by the mid to late 90s a lot of production could be done in the home. Where as before, alienated young creative types wishing to make a dramatic impact literally picked up scraps of the industrial world around them, a new generation had grown up in a very different world, most notably with computers.

It is the opinion of this writer that- while this did result in the creation of a lot of good electronic music across the decade- these technological advances worked ultimately to the determent of Industrial music. The scrap metal pounding lived on as a sample laid over a snare on a drum track to give it a bit of an edge. But live shows began to suffer greatly. Gone were dramatic line ups of several people all banging on things to give a show its live energy. More and more "bands" consisted of two people- one of them singing, and the other playing a keyboard over backing tracks (including drums) pre-recorded onto a DAT tape- or more recently- an ipod or a laptop. Even if they are dressed up to be scary, the clothes and camo netting has about a 99.8% failure rate to make up for the amount of energy lost by

1) Having no drummer to bang on stuff

2) Having "musicians" stand in one place throughout the entire show

3) The audience's inability to determine whether or not the "performers" are actually playing anything live at all, just standing there doing nothing, faking it, or what.

* * *

Subject matter shifted a bit as well. Part of this was driven by the natural inclination of any scene to innovate, but it is important to understand the material changes taking place in the societies where this music was being written. The neo-liberal, "post industrial", world of computers and subsequent alienation brought with it a different set of themes that what had predominated earlier. Laibach was formed in mirror opposition to a state which after 1991 no longer existed. The threat of world war between the super powers that was the principle inspiration for 50 years of apocalyptic fiction was for a time rescinded, and above all the "industrial" jobs had since the 70's been increasingly exported from the developed world.

Dirt, sweat, repression, steel toes, and cold hard machinery were increasingly disconnected from the every day experiences of western citizens in the days of Clintonoid complacency. The alienation of computer life, with the corresponding fantasies of cyberpunk, serial killers, and cybernetics combined to update "clunky" 80s apocalypticism with a colder, more efficient dystopian vision. The 1980s gave us The Terminator. By 1999 we had The Matrix.

Electronica became an ever more dominant form within the scene and by the late 1990s it had pretty much pushed the old "banging on scrap metal" aesthetic out completely. The long term negative impact that this trend would have upon the quality of live shows was not immediately appreciated. An identity crisis was brewing, but for a time a period of uncertainty and potential predominated.

Among the most promising and interesting bands of this period I will mention Velvet Acid Christ, Haujobb, Wumpscut, Funker Vogt, Das Ich, and Brain Leisure. For audio examples:

Malfunction by VAC:

Defect by Brain Leisure:

The aforementioned Wumpscut and Das Ich were part of the "Neue Deutsche Todeskunst" (New German Death Art) movement in the early 90s, where much of the darkest "goth-industrial" music of the decade originated.

Soylent Green by Wumpscut:

Jericho by Das Ich:

These groups all showed a lot of potential. Unfortunately, much of it would be drowned out and sidelined by the rise of new challenges in the 2000s.

As a counter cultural movement, Industrial Music's trajectory became ever narrower the more it grew and began to institutionalize itself. As with all movements, the growth of this scene to a broadness sufficient to justify structural organization would ultimately encourage conservatism and stifle experimentation. Independently minded creative people, interacting with an ascending scene and with each other, can push themselves to all sorts of fascinating results. When industrial grew and became club centered, participants were pressured to abandon "doing one's own thing" with regards to fashion or life style. Patrons expected DJs to furnish danceable hits and DJs expected to get paid and be invited back the next week. This naturally elevated certain forms and discouraged others.

Along with clubs, commercialization led to the marketing of a certain image, and the centrality of dance clubs reinforced its importance. Pretty soon young people looking for something to rebel to were getting sold a way to dress and a music to listen to that they themselves had contributed to very little. The same thing of course happened to the Hardcore Punk scene. Any 15 year old wanting to fit in with it today has no choice but to wear exactly the same thing that people thirty years ago were wearing (many of whom are today quite dead).

* * *

In the 2000's two things happened which I believe have firmly entrenched "Industrial" within the final, parodic phase of its own death agony.

1) Future Pop took over

VNV nation is a band that released a kind of interesting war inspired electronic album called Advance and Follow in 1995. It then became a synth pop band with super repetitive synth parts and super repetitive drum patterns, and a bald fat singer who sings prettily about how much he is in love with you. This crap is totally lame and at least one song from them has been played every night at 90% of "goth-industrial" clubs in the United States for the past nine years.

EX: Beloved, from the album "Futureperfect"

The album "Futureperfect" coined the term, "Future Pop", which can be used to describe this kind of stuff. Other synthpop bands, such as Apoptgyma Berzerk, Beborn Beton, Diary of Dreams, Blutengel, etc... have a similar sound and feel. They are not industrial at all... yet they have taken over a lot of Industrial's market share.

2) Terror EBM

The sardonic twin of Future Pop is "Terror EBM". It has a very similar musical form of repetitive synth parts, and repetitive drums, and a singer. However it is slightly "harder", and the songs attempt to be a bit "scary". Suicide Commando's 1999 "Mindstrip" album is a good example of this sub genre's emergence.

However, so many bands imitated this sound, with white face make up and fake blood to boot, that they very quickly killed any interesting potential in it at all. A good example of the depths to which it has sunk sense then is CombiChrist, probably the quintessential generically "hard" and "scary" band with super repetitive songs and beaten to death fake blood, white make up, and "goth chick" / club sex(ist) glamor. For example:

What the hell kind of message is that? Basically... "here is something that's easy to dance to. Look weird and go fuck some goth chick". This kind of objectifying sex-centered ego stroking belongs at a hooters' wet t shirt contest, not an "industrial" club.

A third new emergence, similar to Terror EBM, is to be found amid the "Noise" and "Powernoise" sub genres. Characterized by loud distorted drums, static, and little else, this promised to offer industrial a third, more interesting alternative in the early 2000s. However what actually occurred was that several thousand musicians across the world were all creating very similar albums, and with few exceptions many such "band"'s performances just consisted of one person sitting behind a laptop.

A lot of effort (at the computer) was put into creating an "intense" song. Very little social effort was put into recruiting bandmates to make live performances worth watching.

One good examples of a power noise bands operating today that actually points on a decent show with live drummers is Alter Der Ruine.

This brings us relatively up to date. Music at established dance clubs (For ex: The Church and The Shelter [milk bar] and Disintegration [Benders] in Denver) spend 90% of their time playing Future Pop, some generic Terror EBM, or just some random crappy mixture of the two. To see what I mean... here are two of the worst songs ever written by a band so terrible I will not even mention their name:

These two songs tend to get heavy rotation at most "industrial" nights in the United States.

People there tend to dress almost elusively in clothes that are not suitable for wandering around in any actually industrial place.

Occasionally an old school track is played, but for the most part DJs like to stick to predictable hits.

Around the margins and off the radar there are a few artists creating interesting music, and there are more than a few zines with passionate, unpaid staff writers spending a lot of time trying to get the word out about them. But it is always an uphill battle to shift anything as stuck in its ways as the beast with whom we are now dealing.

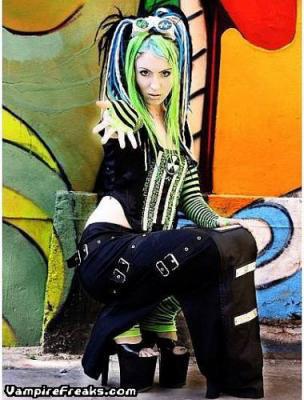

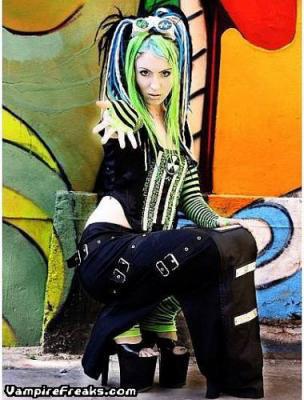

The above picture is what "cyber goth" people look like. This is how many people are dressed today when you go to an "industrial" club. You will notice

1) Shoes are completely unsuitable for protecting one's feet from fuel spills, equipment falls, the shin of an enemy you must kick, etc... and will not help you to run away efficiently from security guards / police / Christians / cyborgs.

2) Hair would be a safety hazard in any "industrial" environment, past, present, or future. So how does wearing safety goggles make sense here?

3) Woman looks a bit sexually objectified

4) Woman would appear a mystically deep, intelligent spirit-guide at Burning Man.

How would you sarcastically mock a club full of people who look like that? Perhaps by dressing as they do but even more ridiculously outlandish so as to draw attention to the absurdity of what they are doing? Well, that isn't really possible... and even if you tried, they'd think you were just trying to be a slightly hipper version of themselves.

When you can no longer mock a scene by sarcastically over inflating its own pretensions, the scene has entered its Parodic phase. Any attempt to "seriously" continue along its own trajectory is indistinguishable from what an attempt to satirize it would be.

Does this mean Industrial is dead?

No.

Exhibit A

( Courtesy http://www.baditudemusic.com/ )

Exhibit B

Those were two clips from bands that are truly embracing the current period. By this I mean their members are thinking people, and they realize this established scene has become pretentious and terrible, and they have broken free from the expected cyber-goth-future-pop-terror-ebm hell. Instead they are consciously subverting these conventions. Baditude does this by coming up with a unique, steroid and weight lifting pro-wrestling approach to EBM. And the second clip, from Alter Der Ruine, escapes the "dark", "scary", "futuristic", "sexy", etc... pretensions by bringing through this video industrial / EBM back to its roots: a few people sitting around who want to have a little fun and dance. The simplicity of the video, decent lighting, apartment setting, and "funny" facial expressions / editing make this way more, well... human and entertaining than the "are you hot enough to fuck me" vibe one gets from watching the earlier CombiChrist video.

It is likely that as more and more "industrial" people with brains catch onto the fact that their scene is completely ridiculous, they will feel the urge to mock it, and we can look forward to the emergence of more parodic industrial bands.

* * *

If I knew the answer to this question I would be too busy off doing whatever it is famous and rich people do instead of writing long articles about the shortcomings of the scene I am a part of.

But here are a few options

1) Try and write the next terrible club hit. Sound as much like CombiChrist as possible. Take yourself seriously and hope people don't notice how ridiculous you are. Make lots of money and have sex with many cyber goth girls. Then kill yourself out of guilt.

2) Write good "old school" / "real" industrial music. Take the effort to put on a real decent show with real drummers and parts being played live and if you must have a singer make sure he isn't ego centric or pretensions. Make real art and bring it to people. Then, starve. Make sure you keep starving and don't do anything rash like applying to Law School which might hinder your ability to starve for the amusement of others.

3) Start a Parodic-Industrial band. Find a unique niche, or invent one like Baditude did. Fuck with people. See if they notice. Maybe they will act differently. Try not to think of Don Quixote comparisons too much. If you develop decent social support networks it might stave off overwhelming despair upon the realization of what your life has become long enough for you to actually get some exposure.

4) Do something new and different that I haven't thought of. Maybe just play guitar a lot and sing. Go find a different genre to hound, or start a new scene. Remember- the best "industrial" musicians were constantly changing and updating their sound, not content to be bound by anyone else's expectations! Controlled Bleeding, anyone?

The following is a list of writing / editorials / music on (/against) the state of industrial that I endorse... because I like the ideas, or because I have written them myself.

Bryan Erickson interview with Baditude

Wounds of the Earth Webzine

Misanthropy vs Activism in Industrial Music

Guide to Saving Industrial: Chapter 1

Review of Unter Null + C/A/T

Should I Hate the DJs or the Club People?

Dj Aesthetic

Buried Electric Records

How to go to a Goth Club

"To escape the horror, bury yourself in it."

-Genet

In the mid to late 1970s a new musical movement, known as punk, emerged in the United States and England, quickly spreading to other countries. The history of Punk itself can, and has, filled volumes, and my purpose is not to recount or critique it here. For our purposes, Punk is significant for ONE reason: It blew the lid off established musical forms and opened the door for a resurgence of innovation.

The number of genres and sub genres that look to punk as musical forefathers is vast. Post-Punk, Hard Rock, Goth, Death Rock, Industrial, EBM, Indie Rock, Emo, Grunge, Metal, Future Pop, Power Noise, etc... all owe a greater or lesser debt to the accomplishments of a rather small number of people banging their fists against the mainstream for a couple of years in the 1970s.

The purpose of this document is not to explain all of them, or even to explain the rise and fall of different bands, labels, individuals, and scenes within Industrial Music in depth. For that I will refer you to the rather good Wikipedia article on this topic. Here I am only providing a rough outline to convey the basics of what different phases the genre has passed through, from its origins, to its current parodic death throws.

This transformation can be appreciated by focusing on five distinct periods of development.

I) The First Wave of Industrial Music

II) Electronica + Sampling & The Golden Age of Industrial

III) Evolution + The Aggro-EBM of the late 1990s

IV) The Wilderness

V) Parodic Phase

I The First Wave of Industrial Music

Industrial has traditionally be characterized as a percussion- intensive genre. This is generally true, however it has been as much focused on simple audio experimentation as it has been with the aesthetic of people banging on things. Take Throbbing Gristle- one of the first "industrial" bands. Using effected guitar and bass, primitive synthesizers, tape loops, and random additional instruments, they created very strange sound-collages that did not generally fit into the traditional "song" structure. If Richard Wright of Pink Floyd was one of the first to use synthesizers as an integral part of pop music in the 1970s, Throbbing Gristle, and their peers in this time (Bands such as Cabaret Voltaire, SPK, Monte Cazazza, Einstürzende Neubauten) were still trying to use- anything and everything - to push and break the limits of what we consider "music".

How about replacing an electric guitar with a Jack Hammer? How about using bits of pipe, scrap metal, and oil drums, instead of traditional drum sets? What better way to reflect (or encourage?) the decay of late industrial society than by appropriating the actual material, and organic sounds, of this society? Punk had thrown open the doors for intelligent people to think about fashion, music and art in different ways... but for all its rage and fury punk has also remained one of the most musically conservative of all genres, hardly ever deviated from the traditional "rock" instrument line up. Industrial people were too creative and adventurous to limit themselves to this.

In the early days, synthesizers were A LOT more expensive than they are today. As a result, few people could afford them. There were no computers and Midi Controllers to set up in one's bed room and "mess around" on. Furthermore, Digital Samplers were not readily available until the early 80's and even by then they were in short supply, very expensive, and had very limited memory and sampling rates. If, instead of a traditional "snare" drum, you wanted the sound of metal on concrete, or metal on metal, you had to actually get those real objects and carry them to a show and bang on them then. As a result, live performances of "industrial" bands in the 70s and 80s were generally more interesting than those of "industrial" bands today.

For an example, see the following early Neubauten clip:

Chaotic noises, the clanging of metal, "industrial" clothing, situations, etc... and some tortured screams to boot. The elements are here in place.

Meanwhile in England a very similar group, Test Department, also could not afford synthesizers. As a result they were able to create, in a far more structured and upbeat way, some of the greatest performances in the history of this genre. The following three videos, for Total State Machine, Compulsion, and Gdnask, will leave you with a good idea of what "Industrial Music" was able to accomplish in its early days.

At this point the basic political / worldview that has been shared by most industrial acts since the beginning should be clearly evident. The world is an unjust furnace of heavy breaking things where people toil and die and are kept in check by a system of official repression as well as ideological confusion. Banging on scrap metal "for arts sake" is always fun... but ideology and political confrontation, whether it was in Test Dept's support of the anti-Apartheid movement in South Africa, or Skinny Puppy's animal rights focus and antiwar messaging, Leatherstrip's anti racist and anti religious album Underneath the Laughter, or Laibach's entire existence... a polemical, political agenda has usually been present.

Laibach, the Slovenian group founded in 1980, began in a very similar situation as Test Department, although on the other side of the "Iron Curtain". Living in "Communist" Yugoslavia, a likely method of rebellion would have been something as predictably degenerate and Western as punk. But these four were a lot more subtle in their rebellion. Instead of frontally attacking the edifice of Stalinist dictatorship, they emulated it even more thoroughly than their own Titoist rulers. Officially, Yugoslav society rested on an assumption of shared ownership, sacrifice, and cooperative living. In reality, social class did exist, and it was upheld with force. Laibach seized on the darkest, most extreme totalitarian impulse and developed it in their music, which was a lot harder for the authorities to understand (let alone repress, when outwardly the band was proclaiming their reverence for the state... even while their own exuberance betrays its brutality and shortcomings).

Here is the music video for one of their best songs, off the Opus Dei record. This song, Geburt Einer Nation, is a cover of One Vision by Queen.

The stunning visuals are no isolated coincidence. In 1983 Laibach helped to found Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK), an artists' collective with architectural, graphic design, videography, and musical departments, that assumed the identity and structure of a universal, planned "state", far out doing the official totalitarian one in the thoroughness and order of its vision.

Not surprisingly, Laibach's first releases in the west were met with skepticism, with many confused observers writing them off as some kind of Fascist or Communist hobgoblin. For more on the interesting early days of this project (up to the early 90s), see this wonderful 6 part documentary.

II Electronica + Sampling & The Golden Age of Industrial

If synth-laden "New Wave" secured a dominant position in the pop of the 1980s, the growing accessibility of keyboards and sampling technology brought with it an evil twin who would lurk the shadows throughout the decade. Skinny Puppy, Front 242, Ministry, Revolting Cocks, Numb, The Legendary Pink Dots, KMFDM, My Life With the Thrill Kill Kult, Die Warzau, X Marks the Pedwalk, Leaether Strip, Front Line Assembly... to name a few. Several of these acts originated in Canada, and as this "second wave" of industrial grew into a more coherent scene, the memberships of many different acts would overlap, spinning off a series of guest appearances, side projects, and "supergroups" like Pigface and Revolting Cocks who've left their legacy in countless youtube videos, fanatically collected and traded bootlegs, rare vinyls, and general nostalgia.

Listening to any of these bands you'll quickly notice the important of synthesizers. In addition, the use of samplers meant that, rather than dragging an entire construction site on stage a la Neubauten, one could simply take a tape recorder to the construction site, and later re-create "industrial" soundscapes in the studio. Bands needed less (though still a few) members, but fewer people could sonically accomplish quite a great deal more, running synthesized and recorded ambiance, "found sounds", and yes, even disturbing vocal clippets from films, radio, or television, through a series of filters and multi effects.

This video from "Worlock", is probably Skinny Puppy's best known song. It was banned when released to due to inability to get clearance from so many film studios for lifting clips from horror films. Bootlegs used to be sold back and forth over ebay by fans. Now youtube finally brings it to everyone:

A good way to characterize skinny puppy's sound is "Wet". Erie strings, bloody samples, reverb, delays, etc... are literally dripping off and over a steady beat, as they set out to portray a frightening world as seen from the standpoint of, well... a mistreated dog. This style was developed within Puppy and a series of spin offs and side projects (aDuck, Hilt, Doubting Thomas, the Tear Garden, CyberAktif, oHgr, and Download, to name several).

A bit of a counter point maybe found in the rise of "EBM", or "Electronic Body Music". Using drum machines, at times live drummers, and fast, arpeggiated bass lines and synth leads, this term was first coined by Front 242. While similar in a lot of ways to "wetter", more experimental bands like Numb or Puppy, EBM has generally been "tighter", faster, and more specifically made for the dance floor.

This is really a terribly over-played song... but as pretty much all of 242's official videos are pretty cheezy & 80s, this one is at least a bit more interesting than many.

If you're wondering why the guys in that film look like they are fighter pilots or something, well, that is part of the martial EBM aesthetic. It's ironic that many "industrial" nights now a days alternate playing bands like this, and playing "80s" music that bands like this were in their own time rebelling against. If Duran Duran and Tears for Fears were writing pop songs to dance and have fun with, 242 and Front Line Assembly were interested in a more "martial" approach that engaged with all the frankness (and influences) of a war correspondent what exactly was happening in the world. Naturally many of their songs happened to be about war, and were rather a bit dark with post - apocalyptic themes predominating. Alternately, synthpop was always more concerned with trying to hide from reality- preferably in the comfortable arms of a lover.

As another example, here we have the hit "Plasticity" by FLA:

Within EBM, not all the focus was as dark. A few "Funk-Industrial" bands, like Nitzer Ebb and Die Warzau, developed out broader musical influences in the late 80s:

EX: Strike to the Body by Die Warzau:

In a similar vein, My Life With the Thrill Kill Kult took satanism, drugs, sex, and a drum machine, and turned it all into a rather upbeat dance act:

III Evolution + The Aggro-EBM of the late 1990s

In the 1990s many different things happened to Industrial- some good and some bad- but all were transformative, and it would be impossible to understand the genre today without a look at these processes as they unfolded over the decade.

Of course, a few bands from the early days broke up or took long breaks (though a surprising number continued), and a few drug related deaths did occur (leading most notably to the demise of Skinny Puppy in 1995). Of the bands that remained, a lot began to change their sound, perhaps bowing to commercial pressure by breaking into more commercially acceptable genres, or perhaps simply because it is unrealistic to expect an artist to make the same album every time. Sometimes this worked for the better and sometimes for the worse.

However, commercialization and the watering down of experimental origins certainly did take place.

For example, many fans of "metal" music today know about and love Ministry, which ever since The Land of Rape and Honey album has pretty much relegated electronics to the far sidelines... for all intents and purposes Ministry has been a metal act since then. Prior to this occurrence, here is a song off the EBM/ industrial album Twitch (1986):

Here's "New World Order" of the later Psalm 69 (1991) album.

You'll notice there's a few faint repetitive sampled sounds that add to the rhythm. But by this point, electronics are pretty much gone, and guitars have taken over.

For an oft-note-and-denounced of example of commercialization, see "Down In It", by Nine Inch Nails, which lifts the rhythm and guitar part from "Dig It" by Skinny Puppy. While Puppy's track was generally dark, distorted, and far less accessible to the masses, the NIN track is far more polished. If Marilyn Manson cashed in on the latent commercial potential of Goth, NIN more than any other band can be said to have done so for industrial.

* * *

On the plus side, a new generation of musicians who grew up listening to Puppy, FLA, and the Wax Trax! record label were now making their own music, and a lot of it in the mid-late 90s seemed promising. Changes took place both in aesthetics as well as technology. Synthesizers continued to fall in price and by the mid to late 90s a lot of production could be done in the home. Where as before, alienated young creative types wishing to make a dramatic impact literally picked up scraps of the industrial world around them, a new generation had grown up in a very different world, most notably with computers.

It is the opinion of this writer that- while this did result in the creation of a lot of good electronic music across the decade- these technological advances worked ultimately to the determent of Industrial music. The scrap metal pounding lived on as a sample laid over a snare on a drum track to give it a bit of an edge. But live shows began to suffer greatly. Gone were dramatic line ups of several people all banging on things to give a show its live energy. More and more "bands" consisted of two people- one of them singing, and the other playing a keyboard over backing tracks (including drums) pre-recorded onto a DAT tape- or more recently- an ipod or a laptop. Even if they are dressed up to be scary, the clothes and camo netting has about a 99.8% failure rate to make up for the amount of energy lost by

1) Having no drummer to bang on stuff

2) Having "musicians" stand in one place throughout the entire show

3) The audience's inability to determine whether or not the "performers" are actually playing anything live at all, just standing there doing nothing, faking it, or what.

* * *

Subject matter shifted a bit as well. Part of this was driven by the natural inclination of any scene to innovate, but it is important to understand the material changes taking place in the societies where this music was being written. The neo-liberal, "post industrial", world of computers and subsequent alienation brought with it a different set of themes that what had predominated earlier. Laibach was formed in mirror opposition to a state which after 1991 no longer existed. The threat of world war between the super powers that was the principle inspiration for 50 years of apocalyptic fiction was for a time rescinded, and above all the "industrial" jobs had since the 70's been increasingly exported from the developed world.

Dirt, sweat, repression, steel toes, and cold hard machinery were increasingly disconnected from the every day experiences of western citizens in the days of Clintonoid complacency. The alienation of computer life, with the corresponding fantasies of cyberpunk, serial killers, and cybernetics combined to update "clunky" 80s apocalypticism with a colder, more efficient dystopian vision. The 1980s gave us The Terminator. By 1999 we had The Matrix.

Electronica became an ever more dominant form within the scene and by the late 1990s it had pretty much pushed the old "banging on scrap metal" aesthetic out completely. The long term negative impact that this trend would have upon the quality of live shows was not immediately appreciated. An identity crisis was brewing, but for a time a period of uncertainty and potential predominated.

Among the most promising and interesting bands of this period I will mention Velvet Acid Christ, Haujobb, Wumpscut, Funker Vogt, Das Ich, and Brain Leisure. For audio examples:

Malfunction by VAC:

Defect by Brain Leisure:

The aforementioned Wumpscut and Das Ich were part of the "Neue Deutsche Todeskunst" (New German Death Art) movement in the early 90s, where much of the darkest "goth-industrial" music of the decade originated.

Soylent Green by Wumpscut:

Jericho by Das Ich:

These groups all showed a lot of potential. Unfortunately, much of it would be drowned out and sidelined by the rise of new challenges in the 2000s.

IV The Wilderness

As a counter cultural movement, Industrial Music's trajectory became ever narrower the more it grew and began to institutionalize itself. As with all movements, the growth of this scene to a broadness sufficient to justify structural organization would ultimately encourage conservatism and stifle experimentation. Independently minded creative people, interacting with an ascending scene and with each other, can push themselves to all sorts of fascinating results. When industrial grew and became club centered, participants were pressured to abandon "doing one's own thing" with regards to fashion or life style. Patrons expected DJs to furnish danceable hits and DJs expected to get paid and be invited back the next week. This naturally elevated certain forms and discouraged others.

Along with clubs, commercialization led to the marketing of a certain image, and the centrality of dance clubs reinforced its importance. Pretty soon young people looking for something to rebel to were getting sold a way to dress and a music to listen to that they themselves had contributed to very little. The same thing of course happened to the Hardcore Punk scene. Any 15 year old wanting to fit in with it today has no choice but to wear exactly the same thing that people thirty years ago were wearing (many of whom are today quite dead).

* * *

In the 2000's two things happened which I believe have firmly entrenched "Industrial" within the final, parodic phase of its own death agony.

1) Future Pop took over

VNV nation is a band that released a kind of interesting war inspired electronic album called Advance and Follow in 1995. It then became a synth pop band with super repetitive synth parts and super repetitive drum patterns, and a bald fat singer who sings prettily about how much he is in love with you. This crap is totally lame and at least one song from them has been played every night at 90% of "goth-industrial" clubs in the United States for the past nine years.

EX: Beloved, from the album "Futureperfect"

The album "Futureperfect" coined the term, "Future Pop", which can be used to describe this kind of stuff. Other synthpop bands, such as Apoptgyma Berzerk, Beborn Beton, Diary of Dreams, Blutengel, etc... have a similar sound and feel. They are not industrial at all... yet they have taken over a lot of Industrial's market share.

2) Terror EBM

The sardonic twin of Future Pop is "Terror EBM". It has a very similar musical form of repetitive synth parts, and repetitive drums, and a singer. However it is slightly "harder", and the songs attempt to be a bit "scary". Suicide Commando's 1999 "Mindstrip" album is a good example of this sub genre's emergence.

However, so many bands imitated this sound, with white face make up and fake blood to boot, that they very quickly killed any interesting potential in it at all. A good example of the depths to which it has sunk sense then is CombiChrist, probably the quintessential generically "hard" and "scary" band with super repetitive songs and beaten to death fake blood, white make up, and "goth chick" / club sex(ist) glamor. For example:

What the hell kind of message is that? Basically... "here is something that's easy to dance to. Look weird and go fuck some goth chick". This kind of objectifying sex-centered ego stroking belongs at a hooters' wet t shirt contest, not an "industrial" club.

A third new emergence, similar to Terror EBM, is to be found amid the "Noise" and "Powernoise" sub genres. Characterized by loud distorted drums, static, and little else, this promised to offer industrial a third, more interesting alternative in the early 2000s. However what actually occurred was that several thousand musicians across the world were all creating very similar albums, and with few exceptions many such "band"'s performances just consisted of one person sitting behind a laptop.

A lot of effort (at the computer) was put into creating an "intense" song. Very little social effort was put into recruiting bandmates to make live performances worth watching.

One good examples of a power noise bands operating today that actually points on a decent show with live drummers is Alter Der Ruine.

This brings us relatively up to date. Music at established dance clubs (For ex: The Church and The Shelter [milk bar] and Disintegration [Benders] in Denver) spend 90% of their time playing Future Pop, some generic Terror EBM, or just some random crappy mixture of the two. To see what I mean... here are two of the worst songs ever written by a band so terrible I will not even mention their name:

These two songs tend to get heavy rotation at most "industrial" nights in the United States.

People there tend to dress almost elusively in clothes that are not suitable for wandering around in any actually industrial place.

Occasionally an old school track is played, but for the most part DJs like to stick to predictable hits.

Around the margins and off the radar there are a few artists creating interesting music, and there are more than a few zines with passionate, unpaid staff writers spending a lot of time trying to get the word out about them. But it is always an uphill battle to shift anything as stuck in its ways as the beast with whom we are now dealing.

V Parodic Phase

The above picture is what "cyber goth" people look like. This is how many people are dressed today when you go to an "industrial" club. You will notice

1) Shoes are completely unsuitable for protecting one's feet from fuel spills, equipment falls, the shin of an enemy you must kick, etc... and will not help you to run away efficiently from security guards / police / Christians / cyborgs.

2) Hair would be a safety hazard in any "industrial" environment, past, present, or future. So how does wearing safety goggles make sense here?

3) Woman looks a bit sexually objectified

4) Woman would appear a mystically deep, intelligent spirit-guide at Burning Man.

How would you sarcastically mock a club full of people who look like that? Perhaps by dressing as they do but even more ridiculously outlandish so as to draw attention to the absurdity of what they are doing? Well, that isn't really possible... and even if you tried, they'd think you were just trying to be a slightly hipper version of themselves.

When you can no longer mock a scene by sarcastically over inflating its own pretensions, the scene has entered its Parodic phase. Any attempt to "seriously" continue along its own trajectory is indistinguishable from what an attempt to satirize it would be.

Does this mean Industrial is dead?

No.

Exhibit A

( Courtesy http://www.baditudemusic.com/ )

Exhibit B

Those were two clips from bands that are truly embracing the current period. By this I mean their members are thinking people, and they realize this established scene has become pretentious and terrible, and they have broken free from the expected cyber-goth-future-pop-terror-ebm hell. Instead they are consciously subverting these conventions. Baditude does this by coming up with a unique, steroid and weight lifting pro-wrestling approach to EBM. And the second clip, from Alter Der Ruine, escapes the "dark", "scary", "futuristic", "sexy", etc... pretensions by bringing through this video industrial / EBM back to its roots: a few people sitting around who want to have a little fun and dance. The simplicity of the video, decent lighting, apartment setting, and "funny" facial expressions / editing make this way more, well... human and entertaining than the "are you hot enough to fuck me" vibe one gets from watching the earlier CombiChrist video.

It is likely that as more and more "industrial" people with brains catch onto the fact that their scene is completely ridiculous, they will feel the urge to mock it, and we can look forward to the emergence of more parodic industrial bands.

* * *

Epilogue: What's a rivet head to do?

If I knew the answer to this question I would be too busy off doing whatever it is famous and rich people do instead of writing long articles about the shortcomings of the scene I am a part of.

But here are a few options

1) Try and write the next terrible club hit. Sound as much like CombiChrist as possible. Take yourself seriously and hope people don't notice how ridiculous you are. Make lots of money and have sex with many cyber goth girls. Then kill yourself out of guilt.

2) Write good "old school" / "real" industrial music. Take the effort to put on a real decent show with real drummers and parts being played live and if you must have a singer make sure he isn't ego centric or pretensions. Make real art and bring it to people. Then, starve. Make sure you keep starving and don't do anything rash like applying to Law School which might hinder your ability to starve for the amusement of others.

3) Start a Parodic-Industrial band. Find a unique niche, or invent one like Baditude did. Fuck with people. See if they notice. Maybe they will act differently. Try not to think of Don Quixote comparisons too much. If you develop decent social support networks it might stave off overwhelming despair upon the realization of what your life has become long enough for you to actually get some exposure.

4) Do something new and different that I haven't thought of. Maybe just play guitar a lot and sing. Go find a different genre to hound, or start a new scene. Remember- the best "industrial" musicians were constantly changing and updating their sound, not content to be bound by anyone else's expectations! Controlled Bleeding, anyone?

For Further Reading:

The following is a list of writing / editorials / music on (/against) the state of industrial that I endorse... because I like the ideas, or because I have written them myself.

Bryan Erickson interview with Baditude

Wounds of the Earth Webzine

Misanthropy vs Activism in Industrial Music

Guide to Saving Industrial: Chapter 1

Review of Unter Null + C/A/T

Should I Hate the DJs or the Club People?

Dj Aesthetic

Buried Electric Records

How to go to a Goth Club

Saturday, October 10, 2009

Communiqué from an Absent Future

The following document is "critical theory and content from the nascent ucsc occupation movement". It's origional location online is here. You can even download it as a PDF booklet here.

My thoughts.... some of the language here is a little heady and uber theoretical / ideological. But that's probably to be expected if someone from a university is writing it. Those people are trained to write in certain ways... Maybe the title is kinda pretentious(?). And reform / revolution questions get a bit muddled. I think it's great these people have occupied their university, but what will they be doing in a month or a sesmester of 5 years? One of the most important lessons I have learned about politics over the past decade is that NOTHING political proceeds in a linear direction. There are tremendous ups and downs. You're very inspired one day and then very demoralized the next. People come out of the wood work and march with you and take on roles at a certain time... a few weeks later they've disappeared. The hardest and most important part is to be able to find a way to consistently relate to and push forward a political environment that is constantly changing.

That being said, there is a lot in here that is good and needs to be read. A lot of it reminds me of my own criticisms of the state of higher education. This document however is the product of the current recession, and I wholeheartedly endorse the bulk of what it is trying to say, which is, in short, that college has become a farce. You get a degree that there are no jobs for. Getting a degree can even be a liability, because you're suddenly in debt and have less work experiance that people who were working full time out of high school. This document is an attempt to break from that mold, reject the neoliberal model, and embark upon a course to transform the existing order of decay into one that actually values human life.

As a college graduate who was unemployed a lot of last year, and currently makes $11.50 an hour working outside at night when it is 20 degrees, a lot of this hits home hard.

Documents like this being created are a sign of political health and intellectual foment. We need more of them.

-CW

---------

Like the society to which it has played the faithful servant, the university is bankrupt. This bankruptcy is not only financial. It is the index of a more fundamental insolvency, one both political and economic, which has been a long time in the making. No one knows what the university is for anymore. We feel this intuitively. Gone is the old project of creating a cultured and educated citizenry; gone, too, the special advantage the degree-holder once held on the job market. These are now fantasies, spectral residues that cling to the poorly maintained halls.

Incongruous architecture, the ghosts of vanished ideals, the vista of a dead future: these are the remains of the university. Among these remains, most of us are little more than a collection of querulous habits and duties. We go through the motions of our tests and assignments with a kind of thoughtless and immutable obedience propped up by subvocalized resentments. Nothing is interesting, nothing can make itself felt. The world-historical with its pageant of catastrophe is no more real than the windows in which it appears.

For those whose adolescence was poisoned by the nationalist hysteria following September 11th, public speech is nothing but a series of lies and public space a place where things might explode (though they never do). Afflicted by the vague desire for something to happen—without ever imagining we could make it happen ourselves—we were rescued by the bland homogeneity of the internet, finding refuge among friends we never see, whose entire existence is a series of exclamations and silly pictures, whose only discourse is the gossip of commodities. Safety, then, and comfort have been our watchwords. We slide through the flesh world without being touched or moved. We shepherd our emptiness from place to place.

But we can be grateful for our destitution: demystification is now a condition, not a project. University life finally appears as just what it has always been: a machine for producing compliant producers and consumers. Even leisure is a form of job training. The idiot crew of the frat houses drink themselves into a stupor with all the dedication of lawyers working late at the office. Kids who smoked weed and cut class in high-school now pop Adderall and get to work. We power the diploma factory on the treadmills in the gym. We run tirelessly in elliptical circles.

It makes little sense, then, to think of the university as an ivory tower in Arcadia, as either idyllic or idle. “Work hard, play hard” has been the over-eager motto of a generation in training for…what?—drawing hearts in cappuccino foam or plugging names and numbers into databases. The gleaming techno-future of American capitalism was long ago packed up and sold to China for a few more years of borrowed junk. A university diploma is now worth no more than a share in General Motors.

We work and we borrow in order to work and to borrow. And the jobs we work toward are the jobs we already have. Close to three quarters of students work while in school, many full-time; for most, the level of employment we obtain while students is the same that awaits after graduation. Meanwhile, what we acquire isn’t education; it’s debt. We work to make money we have already spent, and our future labor has already been sold on the worst market around. Average student loan debt rose 20 percent in the first five years of the twenty-first century—80-100 percent for students of color. Student loan volume—a figure inversely proportional to state funding for education—rose by nearly 800 percent from 1977 to 2003. What our borrowed tuition buys is the privilege of making monthly payments for the rest of our lives. What we learn is the choreography of credit: you can’t walk to class without being offered another piece of plastic charging 20 percent interest. Yesterday’s finance majors buy their summer homes with the bleak futures of today’s humanities majors.

This is the prospect for which we have been preparing since grade-school. Those of us who came here to have our privilege notarized surrendered our youth to a barrage of tutors, a battery of psychological tests, obligatory public service ops—the cynical compilation of half-truths toward a well-rounded application profile. No wonder we set about destroying ourselves the second we escape the cattle prod of parental admonition. On the other hand, those of us who came here to transcend the economic and social disadvantages of our families know that for every one of us who “makes it,” ten more take our place—that the logic here is zero-sum. And anyway, socioeconomic status remains the best predictor of student achievement. Those of us the demographics call “immigrants,” “minorities,” and “people of color” have been told to believe in the aristocracy of merit. But we know we are hated not despite our achievements, but precisely because of them. And we know that the circuits through which we might free ourselves from the violence of our origins only reproduce the misery of the past in the present for others, elsewhere.

If the university teaches us primarily how to be in debt, how to waste our labor power, how to fall prey to petty anxieties, it thereby teaches us how to be consumers. Education is a commodity like everything else that we want without caring for. It is a thing, and it makes its purchasers into things. One’s future position in the system, one’s relation to others, is purchased first with money and then with the demonstration of obedience. First we pay, then we “work hard.” And there is the split: one is both the commander and the commanded, consumer and consumed. It is the system itself which one obeys, the cold buildings that enforce subservience. Those who teach are treated with all the respect of an automated messaging system. Only the logic of customer satisfaction obtains here: was the course easy? Was the teacher hot? Could any stupid asshole get an A? What’s the point of acquiring knowledge when it can be called up with a few keystokes? Who needs memory when we have the internet? A training in thought? You can’t be serious. A moral preparation? There are anti-depressants for that.

Meanwhile the graduate students, supposedly the most politically enlightened among us, are also the most obedient. The “vocation” for which they labor is nothing other than a fantasy of falling off the grid, or out of the labor market. Every grad student is a would be Robinson Crusoe, dreaming of an island economy subtracted from the exigencies of the market. But this fantasy is itself sustained through an unremitting submission to the market. There is no longer the least felt contradiction in teaching a totalizing critique of capitalism by day and polishing one’s job talk by night. That our pleasure is our labor only makes our symptoms more manageable. Aesthetics and politics collapse courtesy of the substitution of ideology for history: booze and beaux arts and another seminar on the question of being, the steady blur of typeface, each pixel paid for by somebody somewhere, some not-me, not-here, where all that appears is good and all goods appear attainable by credit.

Graduate school is simply the faded remnant of a feudal system adapted to the logic of capitalism—from the commanding heights of the star professors to the serried ranks of teaching assistants and adjuncts paid mostly in bad faith. A kind of monasticism predominates here, with all the Gothic rituals of a Benedictine abbey, and all the strange theological claims for the nobility of this work, its essential altruism. The underlings are only too happy to play apprentice to the masters, unable to do the math indicating that nine-tenths of us will teach 4 courses every semester to pad the paychecks of the one-tenth who sustain the fiction that we can all be the one. Of course I will be the star, I will get the tenure-track job in a large city and move into a newly gentrified neighborhood.

We end up interpreting Marx’s 11th thesis on Feuerbach: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.” At best, we learn the phoenix-like skill of coming to the very limits of critique and perishing there, only to begin again at the seemingly ineradicable root. We admire the first part of this performance: it lights our way. But we want the tools to break through that point of suicidal thought, its hinge in practice.

The same people who practice “critique” are also the most susceptible to cynicism. But if cynicism is simply the inverted form of enthusiasm, then beneath every frustrated leftist academic is a latent radical. The shoulder shrug, the dulled face, the squirm of embarrassment when discussing the fact that the US murdered a million Iraqis between 2003 and 2006, that every last dime squeezed from America’s poorest citizens is fed to the banking industry, that the seas will rise, billions will die and there’s nothing we can do about it—this discomfited posture comes from feeling oneself pulled between the is and the ought of current left thought. One feels that there is no alternative, and yet, on the other hand, that another world is possible.

We will not be so petulant. The synthesis of these positions is right in front of us: another world is not possible; it is necessary. The ought and the is are one. The collapse of the global economy is here and now.

II

The university has no history of its own; its history is the history of capital. Its essential function is the reproduction of the relationship between capital and labor. Though not a proper corporation that can be bought and sold, that pays revenue to its investors, the public university nonetheless carries out this function as efficiently as possible by approximating ever more closely the corporate form of its bedfellows. What we are witnessing now is the endgame of this process, whereby the façade of the educational institution gives way altogether to corporate streamlining.

Even in the golden age of capitalism that followed after World War II and lasted until the late 1960s, the liberal university was already subordinated to capital. At the apex of public funding for higher education, in the 1950s, the university was already being redesigned to produce technocrats with the skill-sets necessary to defeat “communism” and sustain US hegemony. Its role during the Cold War was to legitimate liberal democracy and to reproduce an imaginary society of free and equal citizens—precisely because no one was free and no one was equal.